C Generics

Introduction

If you’ve coded in C for any amount of time you probably think that C doesn’t have generics. After all, C++ clearly has generics, so if C did surely they would look the same, right?

Well, you are sort of right, and sort of wrong. See, C does not have generics in the regular sense, where the compiler will figure out which types you are using at compile time and generate the correct code for the generic function or data structure. C has _Generic, which is a compile time macro that chooses between a set list of options based on the type of the argument it was passed.

You may ask, how is this any different from an overloaded function? From what I can tell they’re the exact same thing, with both choosing the correct path at compile time. Sounds simple enough, let’s just use function overloading instead.

int add(int a, int b) { return a + b; } float add(float a, float b) { return a + b; } int main() { int i_result = add(2, 4); float f_result = add(2.0, 4.0); }

12:7: error: conflicting types for ‘add’; have ‘float(float, float)’ 12 | float add(float a, float b) { | ^~~ 8:5: note: previous definition of ‘add’ with type ‘int(int, int)’ 8 | int add(int a, int b) { | ^~~

Ohh… that didn’t work.

As you may know, we don’t have the ability to define overloaded functions in C. This example is small, but imagine having to call an entirely different min or max function for each different type of comparison, it would make your unnecessarily large. We can fix this add example fairly easily.

#include <stdio.h> #define add(a, b) \ _Generic((a), \ int: add_int, \ double: add_double) (a,b) int add_int(int a, int b) { return a + b; } double add_double(double a, double b) { return a + b; } int main() { int res_a = add(3, 4); double res_b = add(3.0, 4.0); printf("int: %d\n", res_a); printf("double: %f\n", res_b); }

int: 7 double: 7.000000

We will quickly break this down before we get in to more complicated implementations later.

#define add(a, b), we start by defining our macro named “add”, which takes 2 parameters `a` and `b`_Generic((a), int: add_int, double: add_double), this is our compile time “switch statement”, which chooses the correct function based on the type of the first argument `a`(a,b), the last block tells the compiler that we are passing the arguments `a` and `b` to the selected function

In this article we are going to take a look at a couple of example use cases where generics may help us write more concise code, that vastly simplifies our API.

Making a better Print Function

Any C programmer has learned to either love or hate printf, I personally prefer it over a C++ ostream, but as I’ve learned from other languages, there can an even easier way to print. In both javascript and vlang you can use the concept of template literals (mdn, vlang). Template literals allow the entire string to be defined at once, with each variable or expression residing within a ${} block.

js

const name = "John"; const age = 32 console.log(`Hi there my name is ${name} and I am ${age} years old.`)

Hi there my name is John and I am 32 years old.

v

name := "John" age := 32 println('Hi there my name is ${name} and I am ${age} years old.')

Hi there my name is John and I am 32 years old.

The ability to place variables inline with the rest of the string increases the speed of iteration, and avoids errors that may occur with a format specifier does not match its argument. It would be really nice if we had this in C, even if it just used for debugging and development.

Let’s see how we can use _Generic to achieve a similar behavior to what we saw above.

Implementation

Our first step is to figure out how we can convert different data types into their string representation. This is where _Generic will be used in our implementation.

#define $(var) \ _Generic((var), \ int8_t: auto_asprintf("%d", var), \ int16_t: auto_asprintf("%d", var), \ int32_t: auto_asprintf("%d", var), \ int64_t: auto_asprintf("%ld", var), \ uint8_t: auto_asprintf("%u", var), \ uint16_t: auto_asprintf("%u", var), \ uint32_t: auto_asprintf("%u", var), \ uint64_t: auto_asprintf("%lu", var), \ float: auto_asprintf("%f", var), \ double: auto_asprintf("%f", var), \ char *: auto_asprintf("%s", var), \ const char *: auto_asprintf("%s", var))

There are a lot of line here, but the logic isn’t too complex. We start out with the function macro definition `$`, keeping the same symbol as we saw with js/v above. This function accepts one parameter, which we will then use to dispatch to the various iterations of auto_asprintf below. The only difference here is what is being passed as the function.

Now we can take a look at this auto_asprintf function, which essentially wraps asprintf to return a char* directly. This will make our life much easier when it comes to printing, and freeing the allocated memory.

char *auto_asprintf(const char *format, ...) { va_list args; va_start(args, format); char *str = NULL; int length = vasprintf(&str, format, args); va_end(args); if (length == -1) { fprintf(stderr, "Failed to allocate memory\n"); return NULL; } return str; }

All we do is wrap asprintf, check for memory allocation errors, and return the string pointer. We use a variadic function here, which I will explain in just a moment.

I guess now would be a good time to look at how we intend to use our new print function. This should give us a better idea of how to implement the behavior.

int main() { println($(5), $(" "), $(3.14)); }

Not the prettiest print function ever, but maybe it’s better than printf (It’s not, I’m just optimistic the DX will be better). So println will be a variadic function taking any number of arguments, then printing them out. You have certainly used a variadic function before, but it is unlikely you have had to write one.

void println(int num_args, ...) { char buf[4096] = {0}; char *pos = buf; va_list args; va_start(args, num_args); for (int i = 0; i < num_args; i++) { char *str_val = va_arg(args, char *); pos = stpcpy(pos, str_val); free(str_val); } va_end(args); *pos++ = '\n'; *pos = '\0'; ssize_t bytes_written = write(STDOUT_FILENO, buf, pos - buf); if (bytes_written == -1) { perror("write"); exit(1); } }

- A variadic function is characterized by its last argument being

..., which represents its list of any number of arguments (although it is limited to 127) - To reference any of the elements in this last we first need a

va_list, which we then initialize withva_start - The arguments are then looped through, with the ability to extract one argument at a time with

va_arg(args, typename) - To clean up resources

va_endis called one you are done with the list

You may notice something I omitted in the explanation, the number of arguments. In C there is no way at compile or run time to get the number of arguments in a va_list. Well that sucks.

So now our users will have to make their first argument the number of arguments. That seems a bit redundant, and now we’re not looking much better than printf.

int main() { println(3, $(5), $(" "), $(3.14)); // ^ // 3 arguments being passed }

5 3.140000

There we go! A slight improvement over printf? Maybe? Either way it was good to explore the use of _Generic. It reminds me a bit more of C++ ostream than I would like, but I can get over that. My biggest gripe here are that spaces have to be specified manually by inserting " " in between variables. That is a challenge that is probably best solved in another language, at another time.

Improvements

Earlier I mentioned how having to specify the number of arguments seems a bit redundant. Can we solve this? We can!

We said that variadic functions can take up to a maximum of 127 arguments, so maybe there is a way we can hard code 127 unique values. This is going to be a very hacky macro, and is totally optional, but it will make the user experience better.

// Helper macro for counting the number of arguments #define NUM_ARGS(...) \ NUM_ARGS_IMPL(__VA_ARGS__, 127, 126, 125, 124, 123, 122, 121, 120, 119, 118, \ 117, 116, 115, 114, 113, 112, 111, 110, 109, 108, 107, 106, \ 105, 104, 103, 102, 101, 100, 99, 98, 97, 96, 95, 94, 93, 92, \ 91, 90, 89, 88, 87, 86, 85, 84, 83, 82, 81, 80, 79, 78, 77, \ 76, 75, 74, 73, 72, 71, 70, 69, 68, 67, 66, 65, 64, 63, 62, \ 61, 60, 59, 58, 57, 56, 55, 54, 53, 52, 51, 50, 49, 48, 47, \ 46, 45, 44, 43, 42, 41, 40, 39, 38, 37, 36, 35, 34, 33, 32, \ 31, 30, 29, 28, 27, 26, 25, 24, 23, 22, 21, 20, 19, 18, 17, \ 16, 15, 14, 13, 12, 11, 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1) // Helper macro for expanding the arguments #define NUM_ARGS_IMPL( \ _127, _126, _125, _124, _123, _122, _121, _120, _119, _118, _117, _116, \ _115, _114, _113, _112, _111, _110, _109, _108, _107, _106, _105, _104, \ _103, _102, _101, _100, _99, _98, _97, _96, _95, _94, _93, _92, _91, _90, \ _89, _88, _87, _86, _85, _84, _83, _82, _81, _80, _79, _78, _77, _76, _75, \ _74, _73, _72, _71, _70, _69, _68, _67, _66, _65, _64, _63, _62, _61, _60, \ _59, _58, _57, _56, _55, _54, _53, _52, _51, _50, _49, _48, _47, _46, _45, \ _44, _43, _42, _41, _40, _39, _38, _37, _36, _35, _34, _33, _32, _31, _30, \ _29, _28, _27, _26, _25, _24, _23, _22, _21, _20, _19, _18, _17, _16, _15, \ _14, _13, _12, _11, _10, _9, _8, _7, _6, _5, _4, _3, _2, _1, N, ...) \ N

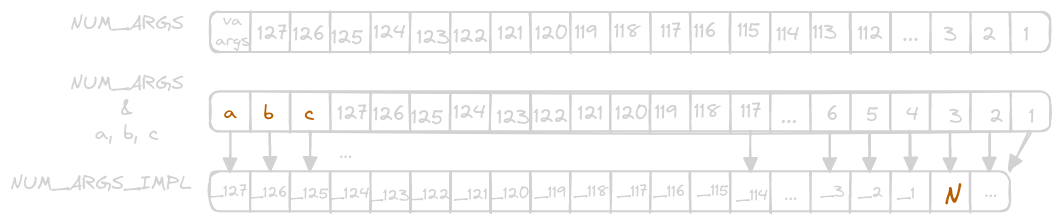

The way this works is a bit complicated, but I will try my best to explain it with the variables a, b, and c

- We call

NUM_ARGS(a, b, c)with all of our arguments - We then call

NUM_ARGS_IMPL(a, b, c, 127, 126, ..., 3, 2, 1) - It may be hard to tell, but

NUM_ARGS_IMPLis a giant function that takes 129 different arguments, named_127-_1,N, and finally its variadic list at the end... a, b, ccauses the original list of numbers to shift to the right by3positions, so that the number in argumentNends up 3! With 2 and 1 spilling off the end into the variadic list- Finally, we are returned the value

3

Now we are able to calculate the number of parameters being passed at compile time, saving our uses from having to explicitly pass the value. If you’ve every heard people complain about macros in C, this is exactly that. Weird and hacky macros to enable meta-programming that was never intended in the C standard.

We should create a wrapper around the 2 new macros to keep our simple to read.

#define println(...) println_impl(NUM_ARGS(__VA_ARGS__), __VA_ARGS__) void println_impl(int num_args, ...) { char buf[4096] = {0}; char *pos = buf; va_list args; va_start(args, num_args); for (int i = 0; i < num_args; i++) { char *str_val = va_arg(args, char *); pos = stpcpy(pos, str_val); free(str_val); } va_end(args); *pos++ = '\n'; *pos = '\0'; ssize_t bytes_written = write(STDOUT_FILENO, buf, pos - buf); if (bytes_written == -1) { perror("write"); exit(1); } }

Our new macro println takes in a variadic number of arguments, passing them first to NUM_ARGS which returns the count, and then calling println_impl with the count, and arguments. That should be all we need to get our print function working, let’s see it in action.

int main() { int a = 5; println($(UINT64_MAX), $(" "), $(INT64_MAX), $(" hi "), $(3.14f), $(" "), $(a)); }

18446744073709551615 9223372036854775807 hi 3.140000 5

Our print function is able to handle all the scalar types, along with basic C-style strings. It has its limitations, namely the ability to specify different formatting than the default, but for development and debugging I find it handy. The code here.

A Generic Vector

We haven’t looked at vectors yet, mostly because they are easy to implement. But what if we were able to create a “generic” vector, that didn’t have to store the elements in an array of void*. We will look at implementing a vector that can hold either int or float values, which of course can easily be expanded by writing more code. Again, C generics are not able to do code generation for us, so the implementation must be written by hand.

I won’t show the entire file here, because it is quite long and repetitive. This really comes down to doing the code generation yourself, which is very time intensive, but will leave you with a clean user interface, and much of the code is copy-pasteable anyway. I tried to write each function in as generic of a style as possible, so that the only things that need to change are the return type, and name.

Implementation

Let’s look at the initialization of a vector, in detail.

#define vector(type) vector_##type typedef struct vector_int { int *data; size_t size; size_t capacity; } vector_int; typedef struct vector_float { float *data; size_t size; size_t capacity; } vector_float;

We have 2 structs here, one for int and the other for float. To get the correct type we use the first macro, which does a simple token concatenation to transform int -> vector_int. The ## specifies that the argument should be place here.

From there we have to initialize the vector, for which we define a function to handle each data type. This is where things start to get repetitive, but I have tried to reduce any changes between functions where possible.

bool vector_int_init(vector_int *v, size_t amount, typeof(*(v->data)) val) { v->data = malloc(amount * sizeof(typeof(*(v->data)))); if (!v->data) { perror("malloc"); return false; } for (size_t i = 0; i < amount; i++) { v->data[i] = val; } v->size = amount; v->capacity = amount; return true; } bool vector_float_init(vector_float *v, size_t amount, typeof(*(v->data)) val) { v->data = malloc(amount * sizeof(typeof(*(v->data)))); if (!v->data) { perror("malloc"); return false; } for (size_t i = 0; i < amount; i++) { v->data[i] = val; } v->size = amount; v->capacity = amount; return true; }

At a high level the only thing we have to change is the functions name, and the specific vector type. Everything else is entirely repeatable because of the compile-time code that we use. typeof() allows us to get the type of any variable, which we use here to specific the type of val. This can be derived from the type of v which is the first argument. The other compile-time feature we use here is sizeof() which returns the size in bytes for any data type.

Other than those 2 parts, this is just regular code you would see for any other vector. Where generics come into play is when we decide which function to call, based on the type of the arguments.

#define vector_init(v, amount, val) \ _Generic((v)->data, int *: vector_int_init, float *: vector_float_init)( \ v, amount, val)

We can “switch” on the type that our vector is holding. So if it holds integers we choose the integer specific function, and the float function otherwise. This allows our users code to look something like this.

int main() { vector(int) v; vector_init(&v, 10, 4); vector(float) f; vector_init(&w, 10, 5.0f); vector_push(&v, 10); vector_push(&f, 7.2f); vector_print(&v); vector_print(&f); }

The rest of our API follows the same pattern, the full code can be seen here, we will just go over the interface.

#define vector(type) vector_##type #define vector_init(v, amount, val) \ _Generic((v)->data, int *: vector_int_init, float *: vector_float_init)( \ v, amount, val) // `v` is unsafe to use after calling unless reinitialized #define vector_destroy(v) \ _Generic((v)->data, \ int *: vector_int_destroy, \ float *: vector_float_destroy)(v) #define vector_push(v, val) \ _Generic((v)->data, int *: vector_int_pb, float *: vector_float_pb)(v, val) #define vector_pop(v) \ _Generic((v)->data, int *: vector_int_pop, float *: vector_float_pop)(v) #define vector_insert(v, pos, val) \ _Generic((v)->data, int *: vector_int_ins, float *: vector_float_ins)( \ v, pos, val) #define vector_delete(v, pos) \ _Generic((v)->data, int *: vector_int_del, float *: vector_float_del)(v, pos) #define vector_str(v) \ _Generic((v)->data, int *: vector_int_str, float *: vector_float_str)(v) #define vector_print(v) \ _Generic((v)->data, int *: vector_int_print, float *: vector_float_print)(v) #define vector_clear(v) \ _Generic((v)->data, int *: vector_int_clear, float *: vector_float_clear)(v) #define vector_stf(v) \ _Generic((v)->data, int *: vector_int_stf, float *: vector_float_stf)(v) #define vector_sort(v) \ _Generic((v)->data, int *: vector_int_sort, float *: vector_float_sort)(v) #define vector_reverse(v) \ _Generic((v)->data, int *: vector_int_rev, float *: vector_float_rev)(v) #define vector_concat(v, w) \ _Generic((v)->data, \ int *: _Generic((w)->data, int *: vector_int_concat, default: error), \ float *: _Generic((w)->data, \ float *: vector_float_concat, \ default: error))(v, w)

Each generic does essentially the exact same thing, choose which function to called upon the type held in v->data. This means that as long as the user passes in a valid vector we will have type safety on the values we attempt to add to it. All that’s left to do is to write all the code that these macro will call. It sounds daunting, but as I said before, most of it can be repeated with minimal changes.

So should you use this in your next C project? If you’re working alone, I don’t see anything wrong with using something like this. If you know the range of types you will need to support it would be simple to implement, and expanding the supported types isn’t too hard as we’ve seen.

Conclusion

_Generic in C is an interesting way to achieve function overloading, which is not normally supported in C. If this is a feature you really need, then _Generic is perfect for you, even allowing you to simplify the API.

Our println function allows the printing of the scalar data types, with an “easier” API than printf.

Our generic vector allows for function overloading, creating a simple API for users.

_Generic can’t do code generation, or generate structs for you, so its use case is very narrow. Experiment with it and see if it can improve your code. If this doesn’t work for your use case you can also explore other languages that allow for meta-programming or compile time code execution.